From doom to bloom

Pessimism is rife, with some justification. So how do we start to improve societal prospects?

As Marc Daalder recently reported in Newsroom, a recent IPSOS survey indicated that

“Three in five New Zealanders say our nation is in decline and our society is broken.”

But we aren’t alone. There is a global crisis of confidence. More than half of those surveyed in 28 countries by IPSOS think things are broken, with declining and inequitable social, economic, and political prospects. A view that is shared across age groups.

In Daalder’s article Paul Spoonley noted the growing global feeling of disenfranchisement and disconnection in many groups and communities. There is also rising anxiousness about political and economic changes.

This is echoed in Edelman’s Trust Barometer, which over the last 15 years shows

“… a slow yet steady decoupling of the mass society from the professional classes, leaders, and those in power.”

Edelman identified a “melange of challenges.” Though to me “melange” sounds too upbeat – like a menu item at a fancy restaurant. Miasma or vortex would be better descriptors of the confounding impacts.

Challenges include:

“War in Europe and the Middle East, conflict in Africa, and major regional tension in Asia. Disinformation. The promise and dystopian threat of AI, and unbounded and unabashed technological innovation. Inflation and the attendant cost of living misery that it brings in many large and legacy economies. Geopolitical competition between global superpowers. The rise of a multi-polar world. And of course, mass migration and its unwelcome sponsors, poverty and climate change.” Edelman Trust Barometer 2024

In addition, there are economic, political and societal polarisations and continuing environmental degradation.

Its been broken for a while

Brad DeLong, in his book “Slouching toward Utopia”, identified 2010, or there abouts, as the end of the economic “good times.” (A review in The Atlantic by Annie Lowrey covers some of the key ideas, as does DeLong’s RNZ interview with Kim Hill).

Productivity and wealth grew exceptionally from 1870, which DeLong attributes to a combination of several post-industrial revolution factors. These included development of vertically integrated corporations (which consolidates supply chain control), the industrial research lab (ie, companies undertaking their own research and development and governments supporting such R&D), modern communication devices, and steam-powered and modular shipping technologies.

But another important factor, as Noah Smith noted, was DeLong’s recognition of the development of new political-economic ideas, and the tensions and dynamics between them.

The end, DeLong suggests, was due to a slowdown in productivity, as well as the failure in redistributing the fabulous wealth generated over the “long 20th Century” (1870 to 2010) and in the political neglect of, or ineffectiveness in addressing, social and environmental justice problems.

Whither Aotearoa?

The critical issue for Aotearoa NZ, and elsewhere, is how communities, businesses, and politicians address these challenges, and other issues, to set us on a path that brings better times for all (or at least the many).

Aotearoa NZ doesn’t have a good history of strategic thinking. We can have great ideas, but not the strategic planning and resourcing to make the most of them. Typically too, our political focus has been on shifting policy and funding deckchairs, rather than on more substantive and well-informed changes.

Some commentators on Aotearoa’s approach to defence note our strategic apathy, and that we have “plans masquerading as strategy.” These criticisms apply to other areas of policy too. The government, and many businesses, love reviews and assessments but not long-term expansive thinking or a systemic approach to developing and realising opportunities.

Where’s our mojo strategy?

The NZ Prime Minister, Christopher Luxon, talks about NZ “getting its mojo back” – which I read as greater optimism, innovation, and productivity. But there is no Mojo Strategy, or compelling future vision to inform such a strategy. As I wrote in a previous post, we tend toward political platitudes rather than systemic thinking and action.

Cynics can also argue that muddle rather than mojo is our country’s traditional modus operandi.

A useful framework to help both short and long-term thinking and actions is the OODA Loop model, developed by a military man John Boyd. This stands for:

1. Observe – collecting information on the current situation from as many sources as possible.

2. Orient – analyse this information and use it to update your current reality.

3. Decide – determine a course, or courses, of action.

4. Act – follow through on your decisions.

Aotearoa, generally, seems to be particularly weak on orienting and deciding. This in turn leads to poor follow through, with different governments (and Boards of Directors) changing decisions and directions because there are selective realities and no shared assessment of opportunities and how to realise them.

As Andrew Curry discusses, the analytical mindset and an informed understanding of context and recent history are critical to orient to a new view of the current situation, and potential identifying courses of action.

We tend to look backwards, and in the current global uncertainty this is becoming common elsewhere too. A desire to get back to a higher level of familiarity and certainty. In futures methodology, the futures triangle has a vertex labelled the “weight of the past.” This is supposed to identify sources of constraints and context. However, we are seeing “wait for the past” popping up as a replacement and as the future direction - lets get back to the “good old times”, with a “strong leader” to get us (back) there.

A decade ago, some here and elsewhere were effusing over Aotearoa’s “rockstar economy.” This was based around dairy exports and strong international tourist numbers. Economists, politicians, and others would love to get back to that. They acknowledge it won’t be easy, but can avoid reframing what we should be attempting to achieve.

What doesn’t seem to be widely acknowledged is that the system and context have changed so the country needs to too. We should also move beyond metaphors associated with erratic and destructive behaviours. Despite a “rockstar economy” in the 2010s’ many people didn’t benefit from it.

How can Aotearoa better prepare, adapt and change?

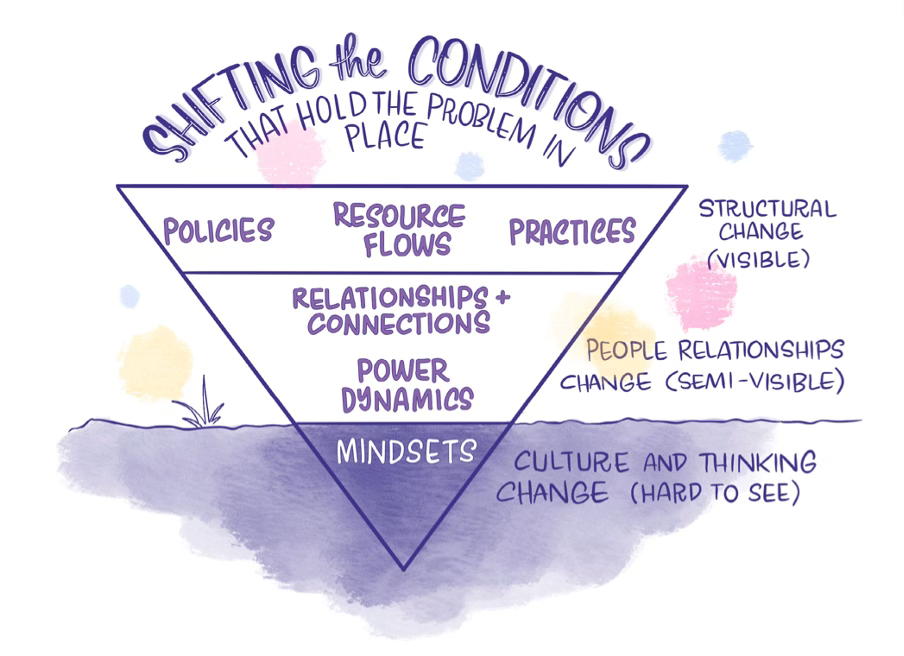

Jess Berentson-Shaw from The Workshop discusses how mindsets and narratives can be changed. Aotearoa tends to focus too much on structural changes, with less attention to relationships and mindsets.

Significant changes or shifts require addressing mindsets and power dynamics. This, The Workshop emphasises, is achieved

“… when groups of concerned and impacted people and their supporters come together in movements to build a strong foundation from which they can amplify helpful narratives. Such movement building is about using structural power, while mindset and narrative shift is about using discursive power — it is together using these two types of power that people have the greatest impact on social change and improving equality”

There are plenty of emerging narratives and actions around (about the economy, transport, housing, the environment, climate change, etc), but many just seem to be small movements focused on particular issues. The risk is that these movements become siloed identities, as James Shaw noted politics is becoming, rather than broad foundations. That isn’t a way to build the discursive power Berentson-Shaw discusses.

There is also a narratives war. Some politicians and business leaders, for example, are trying to undermine the perceived strength of community support about some environmental and social issues (such as climate change and social justice). However, that proclaimed dissension often doesn’t exist. There is strong support for actions to address climate change here, and elsewhere, and in support for the role of the Treaty of Waitangi.

So, the key collective steps should be to develop or strengthen relationships and connections across different narratives and interests to create a more realistic shared view of our current reality and intergenerational aspirations. Then we can work on deciding a common course, and how to start to achieve it.