Is there any point to being a “futurist” today?

The US's geopolitical meltdowns seem to have caught many by surprise; either in their scale and/or the speed. Where's good foresight when you need it most?

I expect many of us, despite the signals of disruption we have observed, are dismayed and at times dumbstruck about the nature and rapidity of change we are experiencing right now.

Governments in Europe, and elsewhere, are scrambling to adjust to the dramatic political changes in the US, though some of these could not only be anticipated, but were explicitly or implicitly signalled by the now President of the USA.

And it’s not because there are fewer people looking toward the future. There are a growing number of scanning and futures reports, wider adoption of foresight methods, and more people offering foresight and futures services. More people now talk about and practice “anticipatory governance.”

So why have we been caught out yet again by fast moving events? Is foresight and futures thinking just a waste of time, effort and money?

No. But of course I would say that. I justify it though by pointing to several challenges with anticipating the future, and how foresight can be strengthened.

I recognise that we may just focus too much on failures, not seeing or acknowledging successful foresight projects. But the apparent failure of European governments to be even slightly prepared for such an American shift is a significant issue. Especially given how much effort Defence and Foreign Affairs agencies are supposed to give to imaging threats and risks.

Four common sources of error

In my first Future Salience post two years ago I discussed how futurists share some common errors with historians:

1. Placing the emphasis on the wrong events;

2. Judging the relative importance of events incorrectly; and

3. Misunderstanding which events had /have the most transformative effects on human life.

And that futurists, unlike historians, are likely to over- and underestimate the scale and pace of change.

Here I use two high profile recent trend reports to illustrate some of these errors, and discuss why avoiding unpalatable developments may be an important issue too.

Bias and short-term self-interest

Two factors that lead to missing or misjudging events are bias and short-termism. This can be deliberate or unintentional and may be because you don’t involve a diverse group of participants or conduct a wider field of scanning, or it just seems top hard. You only see what you want to see. Bias is a common weakness in futures thinking, as is short-termism.

An example of this, is the World Economic Forum’s annual Global Risks Report. As Andrew Curry has noted,

“… every year, it says nothing and it tells you nothing. In other words, much of the sample is drawn from a privileged group whose deformation professional* and general outlook skews them to be more inward looking and short-termist.”

[* a tendency to look at things from the point of view of one's own profession or special expertise, rather than from a broader or humane perspective.]

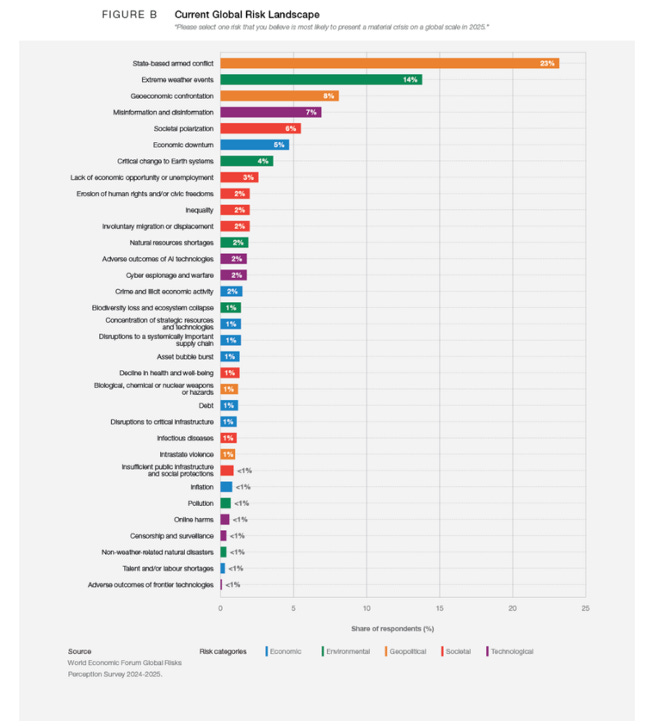

While armed conflict is top of the ranking, vague “geoeconomic confrontation” was seen as a much lesser risk, and rejection of multilateralism is nowhere to be seen. The list of risks is based just on a survey of members, so is simply an elitist vox pop. Anyone reading or listening to the news of the day could come up with a similar list. There is no analysis of assumptions, or what is driving or addressing the risks. It also doesn’t go into what other risks and factors are amplifying individual risks or reducing them.

Some fancy visuals, such as their risk landscape figure (below), imply a sense of depth and rigour. But, as Andrew also commented, since there is often no analytical methodology behind them, they obscure rather than reveal insights. A good report should address questions about “how?”, “why?”, and “what if?”, as well as “what can be done?”

This is performative risk assessment and management. A “name it to tame it” approach – we’ve got it in our risk register with something to indicate we can control or mitigate it. Such reports give a false sense of reassurance that leaders know what is going on and why, and that they will have the time and resources to adapt or manage relevant risks. It can be used, and probably is, to justify avoiding systemic changes.

Such approaches to foresight also fail because they focus on the signs & signals not the system that creates them.

More robust analyses also fail

There are though good analyses out there. The UK’s periodic Global Strategic Trends reports go into considerable detail and involve a broader range of participants and perspectives.

As you’d expect they look closely at geopolitical issues.

“Global power competition. Competition will continue and the balance of power will almost certainly change. Competing actors will include major powers as well as a range of smaller state and non-state actors, which will interact with each other in different ways as they seek to advance their interests and influence.

… It has become increasingly clear that a vast number of uncertainties surround the future landscape of global governance. Central to this is the question of how great power competition will influence international relations and thereby alter the course of events.”

So that’s a fairly generic assessment, written I remind you in the midst of contentious and inflammatory remarks from a US Presidential candidate who previously flouted international norms.

The report also notes the possibility of “… the emergence of a very different world order than that anticipated, shaped by various shocks, developments and the responses of global actors.”

But, as in most futures reports, the potential paces of change aren’t really addressed. The matrix in their Figure 4 above, gives no hint of time or dynamism. In another figure they provide the typical dimensionless timeframe, implying different scenarios may develop relatively sedately.

A more effective futures approach is to break down trends and issues into short- medium- and long-term partitions so timeframes are more explicitly explored. This is often done for implications, but we should also be considering it to question whether our assumptions and expectations for some “wildcard” events occur more or less quickly.

In the conclusion the Global Strategic Trends: Out to 2055 report considers

“Both the US and Canada are likely to maintain their global economic and security footprints out to 2055. The US will strive to retain its economic and military lead, and both countries are likely to remain strong supporters of multilateralism and retain positions of global leadership.”

This was published in September 2024, when the now US President was a strong contender and his intent on disrupting Western norms and multilateral agreements was clear.

It could be that the UK’s Ministry of Defence did consider a rapid geopolitical change but decided not to make that public (for economic and/or diplomatic reasons). However, seeing how they and other European countries are scrambling, it doesn’t look like something they anticipated.

The unpalatability of some events

For me the WEF’s Global Risks Report and the UK’s Global Strategic Trends report are examples of avoiding thinking about the unpalatable. This was a phrase Nic Gowing and Chris Langdon coined in their 2016 Thinking the unthinkable report.

Speaking with business and government leaders they identified nine common themes for why “unthinkable” events (such as the global financial crisis, and Russia’s 2014 invasion of Crimea) were not identified or seriously considered:

1. Being overwhelmed by multiple, intense pressures

2. Institutional conformity

3. Wilful blindness

4. Groupthink

5. Risk aversion

6. Fear of career limiting moves

7. Reactionary mind-sets

8. Denial

9. Cognitive overload and dissonance

On reflection Gowing and Langdon concluded that rather than “unthinkable” they should have called the project “Thinking the unpalatable”. This was because some interviewees did consider “unthinkable” possibilities that came to pass (or could of), but at the time did not think they would be accepted or acceptable because they went against leader and institutional worldviews and mindsets, or because they couldn’t be solved or addressed.

“What gradually became apparent during the large number of interviews is that often enough was known about what was developing. A direction of travel was foreseeable. But those at the top levels did not consider that confronting it was a palatable prospect. On balance, a view was somehow taken that attention was not needed. This was because it was hoped the developing events and scenarios would either somehow vaporise or none of the options for action were sufficiently attractive or practical.”

Gowing and Langdon suggested that at the time senior leadership positions were usually filled with people who had developed their knowledge and experience over a period of slowish and fairly predictable change (conveniently ignoring events such as the 1990’s collapse of Russia, 9/11, and the rise of social media). So, considering rapid or unusual change was possibly something, Gowing & Langdon inferred, that the organisations weren’t familiar or comfortable with, or set up to handle.

Regardless of whether that was true or not then, it definitely isn’t now. But palatability and responsiveness don’t seem to have changed much. Gowing and Langdon built a thriving consultancy to improve thinking about the unthinkable, but it’s hard to argue that they have shifted collective mindsets in the public and private sectors. Incentives and rewards still seem to favour short-term and incremental thinking.

Amara’s Law vs Macmillan’s Law

In the technology world, companies, investors, and pundits often fall victim to Roy Amara’s “law”

“We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.”

In geopolitics, and other areas, we should bear in mind an opposite version. We can underestimate the effects of political (or social) events in the short term. Many futures reports seem to discount or downplay such single “wildcards”, retreating to the comfort of a static composite matrix.

I’ve called this Macmillan’s Law, based on the response of former UK Prime Minister Harold Macmillan (1957-1963) when asked what was the greatest challenge for a statesman. He replied

‘Events, dear boy, events.’

Avoiding fabulism too

Futurists love to talk about “disruptors” and “tipping points”. Though we may often get them wrong, or the nature or time scale of their impacts.

But it can be equally undermining for futures thinkers and practitioners to adopt “Cry wolf” and “The sky is falling” approaches, where we are too quick to label events as disruptive. So that’s where it’s useful to bring in an experienced professional foresight expert. What could really make the sky fall, and how do you communicate that effectively to people who don’t want to accept that contention?

Preparedness not prediction

Good futures work isn’t, after all, about prediction. But what we are seeing and experiencing at the moment suggests that more attention needs to be paid in futures work to exploring potential alternative timeframes for events and “what if?” situations, and their implications. And to not shy away from facing “unthinkable” and “unpalatable” futures.

This can make seemingly implausible or unpalatable events more salient and worthy of consideration, and so help us become better prepared for anticipated, unanticipated, and unpalatable events, as well as opportunities.

To me many futures reports I’ve seen - especially from large organisations - now seem to go for the “palatable” approach. Nothing too contentious. Complexity and chaos filtered out or watered down through tidy graphics. Reassuring (intentionally or not) to the audience. A sense of awareness and control that is undeserved.

The world is getting increasingly messy and chaotic, so futures work needs to capture and communicate that as well.