Seeing less to see more

Futures projects can learn from artists about how to abstract from complexity to better understand the present.

Over this season of indulgence an older post by Matt Schnuck on LinkedIn got me thinking about futures and abstraction.

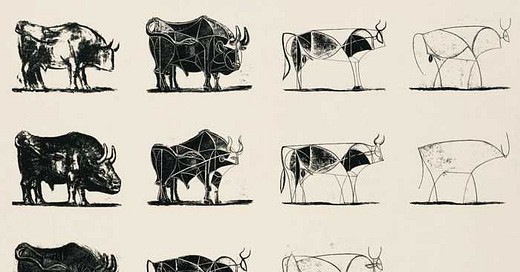

Schnuck claimed that Picasso’s “Bull” lithographs were Steve Jobs’ favourite piece of art, because of Jobs’ obsession with functional simplicity. That’s an unsubstantiated claim. Jobs was also a fan of Kawase Hasui and Japanese shin-hanga prints.

Regardless, if you have a more visual approach to futures thinking then Picasso’s bull lithographs could be helpful. Not because of the minimalist final “bull”, but through the conceptual process to get there.

Unless you are doing speculative futures (“What if ...?”), where the future has little connection to the world of today, then effective foresight needs to be built from the bones and forms of the present.

Futures thinking is a game of two halves. The first is to understand the present and how we got here. The second is to consider future states, and how to prepare for, achieve, or avoid them.

The first half often seems to me to be engaged in too lightly. The “framing” part of foresight is often under-appreciated, with too much of the project typically focussed on collecting information and trend analysis without a clear guiding principle or deep understanding of what has created and maintains the current state.

Following Picasso’s artistic steps can help develop a better picture of what the essentials of the present are to assist in knowing what needs to (or could) change, rather than relying on superficial assumptions and biases.

Both looking at the present and anticipating the future involve consideration of lots of different information and interactions. At the heart of futures is the reduction of complexity. But it’s easy to get lost in the details and stray from the bigger picture, and to over-simplify and lose meaning.

Good futures work is often more art than science, or analytics, because there are subjective choices in what to include, exclude, and highlight. So, futurists can learn from artistic processes.

“Learning how to take complex subjects and simplify them down to abstract forms is a major aspect of art. Most people think that art is all about seeing more detail, but it is really about seeing less. Seeing basic patterns amongst the “noise”; seeing basic forms amongst the complex; seeing the few important details which convey the majority of meaning.” Dan Scott

Futures practitioners can draw on a variety of tools and processes to do this, and create alternative futures. See the UNDP’s Foresight Playbook or UK Gov’s Futures toolkit. However, there is the risk of focussing too much on the tools and just turning one form of complexity into another.

An image, as in Picasso’s case, provides clarity about what you are trying to deconstruct. As well as implying there is an inherent dynamism and unpredictability, which can be lost in the flow charts, system diagrams, and simple graphics that futurists may often employ.

Of course, with a futures project you don’t usually start with a clear image of what you are trying to abstract, you need to do that as part of the framing process.

Abstracting the present

An important aspect in futures is that you are always dealing with constraints. So staying focused on abstracting a metaphorical bull (or other creature) can prevent you from overlooking some key constraints and context.

Artyfactory has a brief discussion of each of the Picasso’s 11 bull lithographs and what they represent. Some of these make sense as futures steps too.

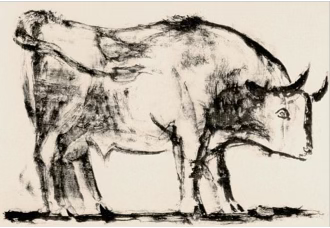

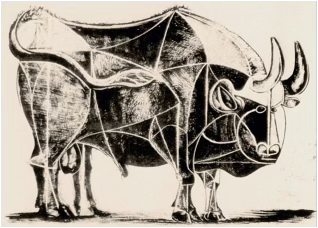

Bull 1 – “Reality”

The bull as commonly seen. This is a starting point for futures work – describing the present, physically, culturally, and behaviourally. Bring together the signs, signals, or “litany” of what we experience. What’s good, what’s improving, what’s disturbing or unusual, and what’s getting worse? What makes sense, what doesn’t, and why?

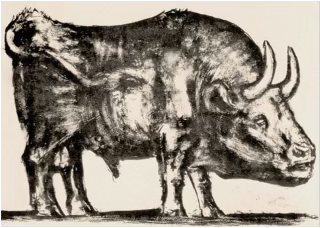

Bull 2 – “Myth”

Picasso exaggerates the bull to emphasise the power and myth associated with the animal. We do that too in our communities and worlds, with different people (and institutions) emphasising or exaggerating different aspects.

For futures work this can be about identifying the underlying myth(s) the current world is built from, and the worldview it generates, as Causal Layered Analysis seeks to uncover.

A good futures approach needs to spend time at the start identifying the different realities and myths about the nature of the beast from participants or clients.

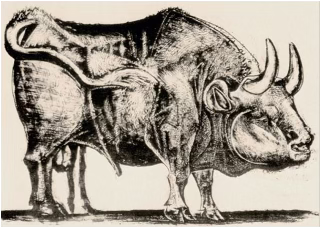

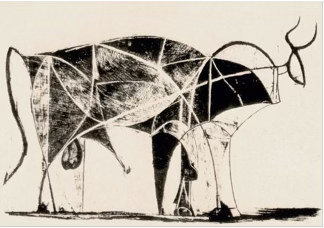

Bull 3 – “Dissection”

Exposing the muscles, skeleton, sinews, and organs. This to me is about identifying the important structures, incentives, constraints, and systems that have shaped and sustain the present (for better or worse). You usually find these by talking with a diverse range of people.

Bull 4 – “Anatomical planes”

The start of simplifying the beast by defining the main planes of anatomy. This can be about seeing how different structures, incentives, constraints, and systems interact with each other – intentionally or unintentionally.

Bull 5 – “Redistribution”

This stage involves reorganising the image to change the dynamics of the front and back and redistributing the animal’s balance. Picasso reduced the size of the bull’s head and emphasised the shifts with the lines.

This could be seen in futures as highlighting where the main strengths and weaknesses of the current system really are, and how they could intersect or avoid each other. The Three Horizons Framework is an obvious tool to employ here, and in the next stage, to help identify what’s failing and what’s emerging that could affect “balance”, or the status quo.

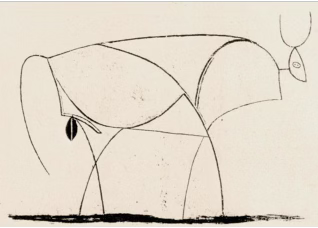

Bull 6 – “Centring”

Picasso inserted counterbalancing lines that point to the centre of balance behind the front legs. This provides (to an artist’s eye at least) a clearer sense of form and function, though there is still a lot going on in the image.

For futures work this stage could be seen as identifying the point(s) where change could have the greatest impacts.

Bulls 7 to 9 – “Outlining & reduction”

Bulls 7, 8 & 9 represent further simplification of form, removing the less important details.

This is where a futurist starts to earn their money, integrating and winnowing out information. This will be informed by experience, more informed advice and opinion, and several futures and strategy tools. But the decisions need to be justified and explainable.

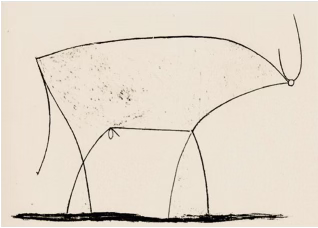

Bull 10 – “Fundamentals”

The shapes and lines that characterise the, or a, nature of the beast. Picasso gives the body more prominence that the head, relative to his first lithographs. Other artists, and futurists, will come to define the fundamentals in their own way.

Bull 11 – “Essence”

The minimalist bull (with genitalia intact, if diminished).

For futures work Number 10 is of more utility than Picasso’s final bull. Eleven is recognisable, but you lose the lines signifying the fundamental forces and how they connect to form. These, rather than just the outline, are what a futurist needs to work with for the second half of the process.

For example, how are environmental and cultural values influencing economic models and government regulations & policies, and vice versa?

Aggregating the future

So, the first half complete. We hopefully have a better understanding of critical features of the present and a distillation of complexity, rather than just relying on biases and unexamined assumptions.

This abstraction process reminds me of one of Richard Rumelt’s strategy essentials in “Good strategy, bad strategy” – having a good diagnosis of the challenge that

“… simplifies the complexity by identifying the critical aspects of the situations… [This diagnosis should] replace the overwhelming complexity of reality with a simpler story, a story that calls attention to its crucial aspects. This simplified model of reality allows one to make sense of the situation and engage in further problem solving.”

The similarity to the artist’s perspective I quoted earlier is obvious.

Bad futures, like bad strategies are often due to a poor diagnosis of the current state.

Developing one or more futures can either involve deconstruction or aggregation processes. The former involves starting with a detail-rich concept of a desirable or undesirable future state. While these can be visionary and inspiring or fearful, they are often ineffective because they lack the distilled complexity to inform how to realistically achieve, or avoid, them. So time and energy is needed to work down to find the minimalistic form that could emerge from the abstracted present.

The second approach is working up from a simplistic form that can be reimagined from the present. Whichever your starting point some of the tools used to explore the present are relevant to constructing futures. Additional foresight tools found in the links I provided above, will also need to be utilised.

In both approaches I don’t think it is that productive to create a fully reimagined future state equivalent to Picasso’s starting bull. Worrying out all the details is complicated, and the future is never as you really anticipate.

More importantly, futures exercises work best when they stimulate and challenge, rather than provide a precisely realised new world. How far back up you move from a minimal future will depend on needs, budget and time.

Picasso’s minimalism approach isn’t the only artistic model to apply to futures. There are other ways to see patterns and signals amidst the noise, and to convey what is meaningful. Futures thinking would benefit from more “artistry” and conceptualism, rather than leaning too much on analytics.

Thinking further and more coarsely.... Perhaps your background in evolutionary biology and mine mired in cattle dung, have more in common than I'd previously appreciated.

Robert, thank you. That's a novel and very thought provoking piece - especially to someone for whom cattle, taurus and indicus, have been a part of so much of their lifetime. It's also interesting when juxtaposed against the strategy that I was taught in earlier years. Enjoyed and appreciated! Tony.