Yesterday's futures and tomorrow's new ideas

In an age of crises we need to be careful we don't fall back on outdated visions and jump to solutions. Instead take time to explore convictions, conflicts, and uncertainties.

Reading most news reports and commentaries, here and elsewhere, there is a dominant doom-laden narrative of everything falling apart. A multi-headed crisis combining political, economic, societal, and environmental disruptions and declines. I wrote about some of this earlier in the year.

People are quick to jump to solutions – civics training, “strong” leaders, end capitalism, “drill, baby, drill!”, degrowth, stop the migrants, etc. That can be the wrong response.

Karl Schroeder, a science fiction writer, suggests that we are trying to address these crises, and flailing, with ideas from the 20th Century.

“I think, in general, we are staggering into our present crises armed with visions of a post-crisis future that are woefully out of date—that are literally from a different century. At some level, we recognize that we’re working to build a future we no longer believe in. It’s our parents’ future, it’s not ours.”

His argument is mostly about old visions of technological futures – rocket ships, robots, driver-less cars, and machine-mind meldings – rather than current crises and how to address them. However, his key point is valid, and similar in aspects to “used futures” that Inayatullah discusses – out-of-date ideas and mindsets.

Uncovering new ideas

What are the new ideas we should be looking at more closely? That is probably the wrong starting question.

Wolfgang Streeck, in 2014, didn’t think we needed to identify what a replacement for capitalism was, it was more important to recognise that one would soon be needed.

“I suggest that we learn to think about capitalism coming to an end without assuming responsibility for answering the question of what one proposes to put in its place.

… While we cannot know when and how exactly capitalism will disappear and what will succeed it, what matters is that no force is on hand that could be expected to reverse the three downward trends in economic growth, social equality and financial stability and end their mutual reinforcement.”

Getting to new ideas

We should also be asking “how do we develop new ideas?”

“What the age calls for is not (as we are so often told) more faith or stronger leadership or more rational organization… Rather is it the opposite: less Messianic ardor, more enlightened skepticism, more toleration of idiosyncrasies, more frequent ad hoc and ephemeral arrangements, more room for the attainment of their personal ends by individuals and by minorities whose tastes and beliefs find (whether rightly or wrongly must not matter) little response among the majority.”

This sounds like it is a recent commentary, but it was in fact a 1950’s suggestion from the political theorist Isaiah Berlin. Surviving the 20th Century, in Berlin’s view, required less conviction and more conversation. That is even more valid at this point in time.

The Workshops’ paper on mindset and narrative shifts is one way to get these conversations going. Another is Jim Ewing’s’ dialogue maps, which he describes in his posthumous book Braving Uncertainty (and discussed by Andrew Curry). Ewing used the maps “to frame transformative conversations” and creating “pathways to clear thinking, productive relationships and more effective action.”

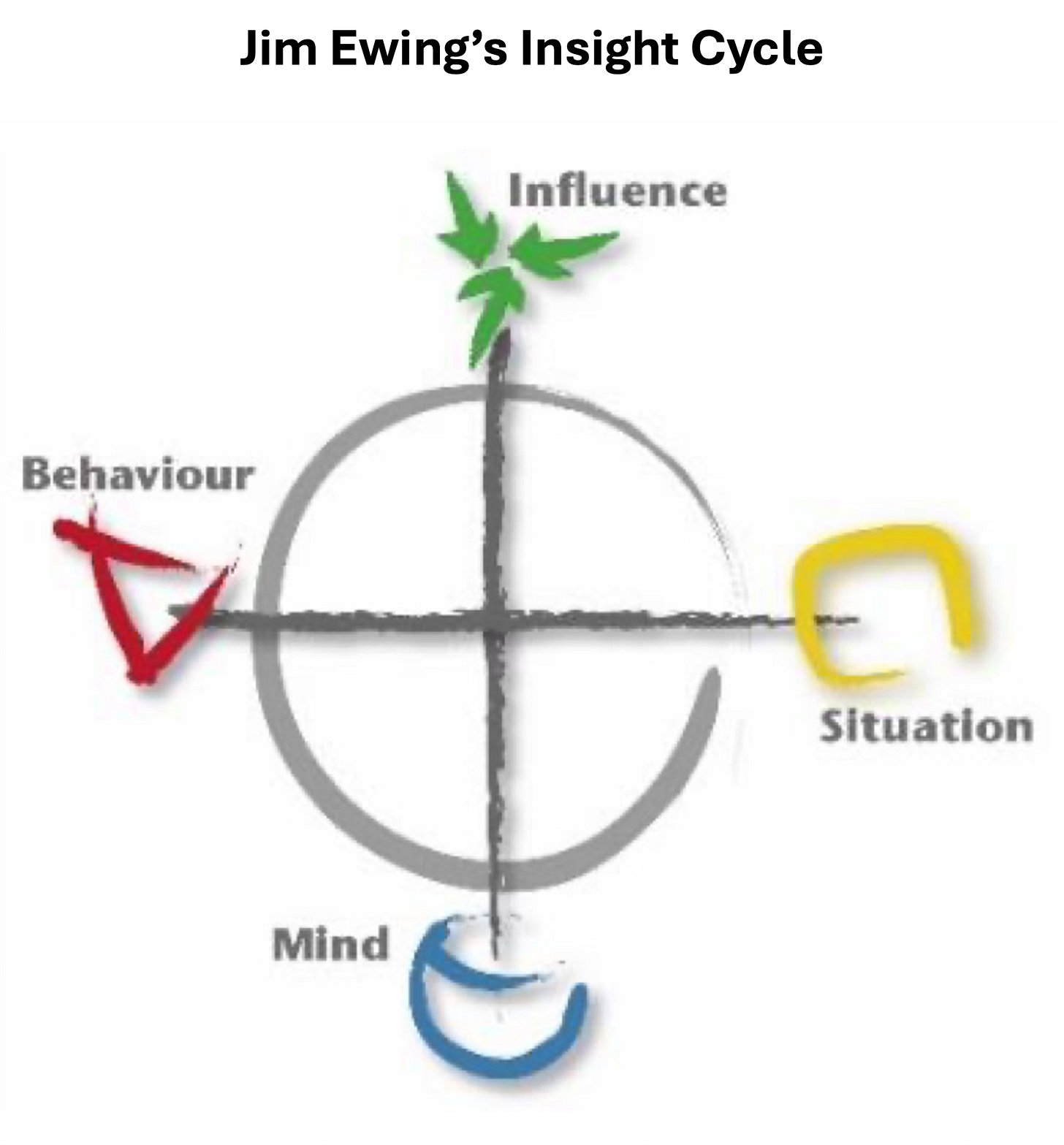

Ewing’s Insight Cycle seems like a great way to start those types of conversations, though I haven’t used it yet.

The cycle includes “Doing” (Behaviour and Situation) and “Being” axes (Influence and Mind), reflecting that how and what we think and believe shape how we act to situations. Situations are “physical conditions, outcomes, results, performance mechanisms…” Mind includes beliefs, assumptions, experience, mental models, regulations, organisation strategies & missions, among other factors.

The Insights Cycle is intended to get people and organisations to more deeply consider how they (or systems) intentionally or unintentionally respond to situations or attempt to shape them. And to get them more comfortable in accepting that a clear answer may not be immediately available.

The Being axis is used to encourage greater “… curiosity, patience, humility, and a willingness to endure uncertainty and ambiguity.” The Doing axis is intended to stimulate discussions about whether we focus too much on acting or being busy, rather than pausing to think whether our actions are appropriate or effective.

Andrew Curry points out that the cycle is not a simple “one workshop and done” activity, ticking off each node and axis. It has conflicts and tensions that need to be revisited, and never really ends. Ewing developed four other maps that work alongside the cycle, which he describes in his book.

In an age of crises, we are tempted to react quickly. But as we have seen with the global financial crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic, those responses can help perpetuate existing structures and systems, rather than creating help usher in a new path to a future that we’d prefer. Futures thinking tools and approaches if done well help us avoid these traps, as long as you embrace inherent uncertainties and are prepared to have your convictions challenged.

[Andrew Curry’s Just Two Things newsletter directed me to Schroeder, Streeck, and Ewing, as his editions frequently do to diverse ideas]